When Brooklyn history teacher Michael Dowd evaluates his ninth graders’ assignments on the Roman Empire, he doesn’t just look for key facts, comprehension and clarity. He scans for the tell-tale signs of artificial intelligence: em-dashes and semicolons, and words like “tapestry,” “delve” and “nuanced.”

Dowd, who teaches at Midwood High School, said he and fellow teachers have developed a lexicon of terms favored by AI.

“There are all these formulaic patterns that happen,” he said. “Kids are cheating.”

But Dowd said he and other teachers have little recourse. He tried feeding students’ assignments through AI detection software last year, but it wasn’t reliable.

Plus, kids use software to disguise when they copy and paste content, sometimes to comical effect.

Dowd said students have turned in papers that refer to the Cuban Rocket Emergency (the Cuban Missile Crisis) or President Shrub (President Bush). Noted Native American war Chief Black Hawk was referred to as Chief Bird of Prey. Dowd’s colleague graded a paper that called the Trail of Tears the Path of Tears.

“It’s obvious,” he said. “But you can’t prove it.”

Dowd’s frustration is shared by many New York City educators. According to the education department, students’ use of AI to cheat is the same as plagiarism, with consequences ranging from parent conferences to suspension.

But in interviews with Gothamist, teachers and advocates said that policy isn’t widely known or easily enforced. They criticized the Department of Education for being slow to respond to AI’s transformation of the education landscape.

“It’s all very murky,” Naveed Hasan, a member of the Panel for Educational Policy, said. “We need to get rules written down.”

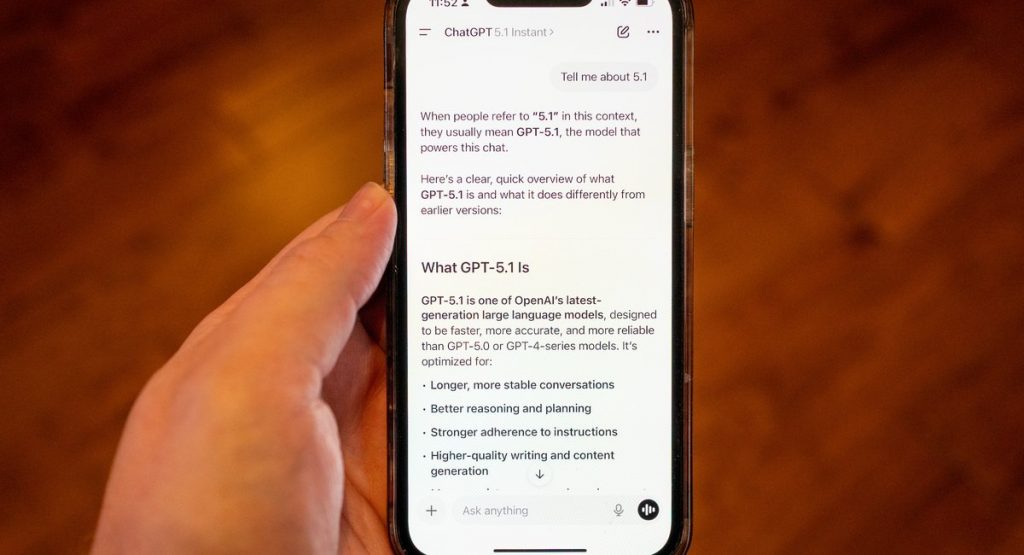

After ChatGPT launched two years ago, the school system banned it, then lifted the ban.

Schools Chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos laid out a vague “framework” that calls for responsible use while tighter guidelines are still being developed. She has convened working groups on the issue to advise on a policy.

In an interview with Gothamist, Aviles-Ramos said formulating clear guidelines for AI should be a top priority that will likely fall to the next mayoral administration.

“It’s here to stay and it’s changing rapidly every day. And the best thing for us to do is to establish guidance around it and face it in a very smart and safe way,” she said.

Critics said the vacuum has led to a flourishing of shortcuts and outright cheating that threaten students’ learning and potentially even their cognitive development.

“I wish they were more forcefully condemning the use of AI for students,” said Mike Stivers, a science teacher at Millennium High School in Brooklyn. “We have no idea what these tools will do to our students’ brains over the long term and by embracing them, we put students’ development at risk.”

Faced with inaction, some elected officials have tried to exert influence.

In November, members of the oversight body the Panel for Educational Policy voted down three proposed contracts for curricula that included artificial intelligence, citing the need for stronger guardrails.

On the state level, Assemblymember Robert Carroll has introduced legislation to ban the use of AI in most kindergarten through eighth-grade classrooms.

Meanwhile, the American Federation of Teachers — which includes the city’s teachers union, the United Federation of Teachers — has launched educator trainings through a partnership with some of the biggest tech companies. The trainings include a call for the protection of student and staff privacy, human jobs, and the environment. But some teachers worry the partnership with Big Tech is a trojan horse for the further intrusion of AI into schools.

Students acknowledged AI is widely used among their peers, but said it’s not always for cheating. Bronx Science senior Keir Horne said he uses AI mostly as a study aid.

“It’s really good for organizing information,” he said. Horne said he often feeds class notes into AI software and asks it to “spit back” questions to help study for tests. He said he has also used AI “to check over essays” or “help figure out a [math] problem.”

“Students usually aren’t writing full papers using AI,” he said. But those who do “will throw in some errors” to make their papers more believable, he said.

Travis Malekpour, who teaches social studies at Cardozo High School in Queens, said a red flag is when students prone to grammatical errors suddenly turn in papers with “advanced collegiate vocabulary.” He said he’s noticed a spike in words like “tapestry” and “plethora.”

Malekpour sometimes uses software from Grammarly to try to detect AI. “It’s not something the DOE provides, but it’s something I’ve been using,” he said.

Generally, Malekpour said, he’s been “steering away” from traditional research papers. He’s assigning more projects instead. In a government class, he now has students go into the community to interview people about various issues.

Dowd said he realizes cheating is not new. Kids used to copy from books, the internet or each other. But he said AI has made it more widespread and challenging to detect. He said it has already transformed the way he teaches.

“I almost never give out take-home assignments now,” he said. Instead, kids are completing coursework in class, often with pen and paper.